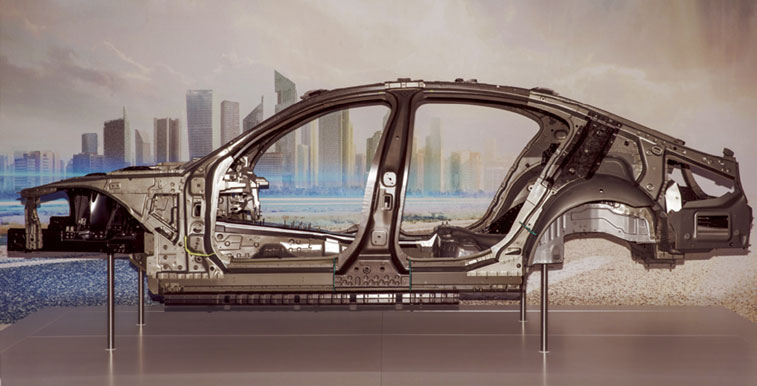

As the automotive manufacturing industry continually advances, so too do the types of materials being used in the construction of vehicles.

At the recent 17th International Automobile Recycling Congress (IARC) held in Berlin, Germany in March, focus was put on the new materials being used in today’s automobiles and how the increased amount of mixed-used plastics may pose challenges to recyclers and dismantlers of end-of-life vehicle.

The increase use of plastics and plastic composites, including carbon fiber-reinforced plastics (CFRPs) is the goal to make cars lighter and thus more fuel efficient.

In today’s automobiles, plastics can be found throughout the vehicle. From windows to taillights, from fuel lines to braking systems, plastic components are readily used in all aspects of vehicle production. Plastics can even be found in lithium polymer car batteries that power some hybrid and electric vehicles.

According to a study by the United Nations Environment Programme, vehicle manufacturing is the most environmentally damaging human activity. Increasingly, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are recognizing resource intensive manufacturing processes are not only hard on wallets but also on the planet.

The latest trends in automotive manufacturing and the changing composition of materials, such as an increased use of mixed plastics and carbon fibers are predicted to pose challenges for end-of-life vehicle dismantlers.

As Diran Apelian, Alcoa-Howmet Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and the founding director of WPI’s Metal Processing Institute, explained, the concept of circular economy is catching on in that manufacturers are addressing the recovery and reuse of materials.

“Manufacturing with the ‘end of life’ in mind has changed the way we design and manufacture,” Apelian said. “Being able to disassemble products at end of life is becoming more and more important. There are some products that are difficult to disassemble, recover and reuse.”

Bill McDonough, one of the authors of the book Cradle to Cradle, called such products: “hybrid monsters.”

“It is our aim to move away from such hybrid monsters and to simplify the way we make things so that they can be reused,” Apelian said. “For example, Kevlar and carbon fiber composites are difficult to recover and reuse, whereas aluminum is so easy. A good example is the Ford F150 truck, which has an all-aluminum body.”

Presently autos are shredded and broken down into two main products: ferrous and nonferrous. Apelian pointed out that this may be too simplistic, and in the future we will need to carry out intelligent sorting to recover certain materials that may be included in the ferrous or in the nonferrous batch that need to be recovered.

“A good example is the rare earth elements that are present in magnets which end up in the ferrous batch when the cars are shredded,” Apelian said. “We are finding that the rare earth metal is ending up in the slag in steelmaking, which is most inefficient. So in brief, intelligent sorting technologies are being developed, and more will be developed in the near future.”

According to Michael Bassipour, president and partner at GLR Advanced Recycling, like in any business, if you don’t adapt to your elements you will not survive. That’s why automotive recyclers need to be aware of the mixed-use materials being used in today’s vehicles so they are readily prepared when these automobiles are ready to dismantle.

“As of today, the increased use of plastics and carbon fibers have had little to no impact on us,” Bassipour said. “We are buying primarily older vehicles, so new materials aren’t relevant and won’t be for at least five to ten years for our business. New markets will inevitably emerge and more sophisticated ways of recycling will always be presented.”

Modified Processes

In addition to the types of mixed-used materials being used in today’s autos, OEMS are also using modified production processes that will also play a role in the eventually recycling of these vehicles.

David Schroeder, director, national accounts, Covanta Environmental Solutions, said the global auto industry is a major consumer of water and we are currently seeing a growing shift towards energy savings and water conservation.

“Look at the painting process, for example, it is both extremely water-intensive and the most expensive component of the automotive assembly plant to build, operate and maintain,” Schroeder said. “It’s also the largest non-hazardous waste stream at facilities.”

As such, we are seeing new technologies enter the paint shop that reduce environmental impact by removing paint particles from the air without the need for chemicals, water or other additives. These paint particles are eliminated from the end-of-life dismantling process as well.

“Processes like these reduce CO2 emissions, energy consumption and water usage, making the painting process a lot less taxing on the planet,” Schroeder said. “Innovation and improvements in automotive manufacturing to reduce OEM’s impact on the environment are at a tipping point and that is carrying over to the way automakers deal with their waste and recycling.”

The EPA’s Design for the Environment program, created to prevent pollution and the risk that pollution presents to humans and the environment, also has come a long way in eliminating hazardous waste streams for end-of-life recycling of automobiles.

One great example is the elimination of mercury in the switches found in many older model vehicles. In addition, Polypropylene (PP) and Polyethylene (HDPE, LDPE) have a strong recycling market; however, certain plastics such as ABS and PVC are still difficult to

recycle.

“End-of-vehicle life continues to be a large focus of concern,” Schroeder said. “Auto shredder residue (ASR) is a large volume stream that continues to be sent to the landfill instead of being reused. Shredded headliner material and other thermal composites remain difficult to handle.”

OEM Efforts With End-of-Life Processes in Mind

When it comes to making meaningful and measureable commitments to managing waste in a more sustainable fashion, the automotive manufacturing industry is leading the way.

As Schroeder explained, an increasing roster of automakers are following the lead of Subaru of Indiana Automotive, Inc. (SIA) – the first automotive assembly plant in the U.S. to achieve zero waste-to-landfill status.

By making the commitment to go zero waste-to-landfill, automakers are committing to ensuring all the solid waste produced at a factory is reused, recycled, composted or recovered for energy generation.

“Between 2000 and 2015, SIA reduced the amount of waste per vehicle produced by 53 percent and cut costs to the tune of millions of dollars each year through adoption of the four “Rs” – reduce, reuse, recycle and recover,” Schroeder said. For the nonhazardous waste left over after efforts to reduce, reuse and recycle are exhausted, SIA ships approximately 4 percent of total waste, or 3,000 tons, to Covanta’s Indianapolis Resource Recovery Facility for disposal, and energy and metal recovery, annually. At Covanta Indianapolis, SIA’s non-hazardous waste is diverted from the landfill and used as fuel to create steam power for Indianapolis’ downtown loop.

Similar to Subaru, Toyota’s North American facilities reduced, reused or recycled 96 percent of their non-regulated waste in 2015 totaling over 900 million pounds by focusing on recycling and reusing.

“They even went so far as to incorporate composting into its sustainability programs to achieve zero waste-to-landfill status,” Schroeder said. “It’s evident that achieving zero waste-to-landfill status is growing in popularity and becoming the industry standard in terms of dealing with waste.”

A Steady Stream

As more than 18 million cars are scrapped per year, and recycling companies continue to modify their processes to handle these ever evolving machines, Bassipour said that his business is steady. “I wouldn’t say ‘growing’ nor ‘dying’ Bassipour said. “Again, if you don’t get creative on buying habits, processing efficiencies, and maximizing your sales, you will fall behind to your competition. It’s a ‘dog eat dog’ industry.”

While auto recyclers continue to feel the impact of lower prices, they are embracing the creativity that Bassipour alludes to in order to offset these lower prices. In addition to entering new areas of recycling, they are being more creative in their recycling process to make it more efficient.

Every day GLR Advanced Recycling reviews and discusses better buying habits and lean processing procedures. They constantly strive to find better ways to process and to buy.

“This is our approach to offset the low metal prices,” Bassipour said. “We also take a hard look at our entire inventory and seek the best consumers that are willing to work with us and our volumes. We are a volume driven operation so every single penny adds up. We are in a very antiquated business and if you don’t change with the times, you will be chasing your tail.”

Indeed, corporations continue to take sustainability seriously, and more customers and users are also following suit. In a circular fashion, corporations are doing well by doing the “right thing” and gaining loyalty of their customers.

“As the consumer continuously demands reduced prices, there is much pressure on manufacturers to reduce their production costs. So recycling processes that are uneconomical will not be adopted,” Apelian said. “The challenge is to develop and discover ways that we can recover and reuse in a way that is economically and commercially feasible. This is what propels us – solutions that are elegant but expensive and that will never be utilized do not interest us here at CR3 (Center for Resource Recovery and Recycling). For solutions to be sustainable, the business model needs to be sustainable.”